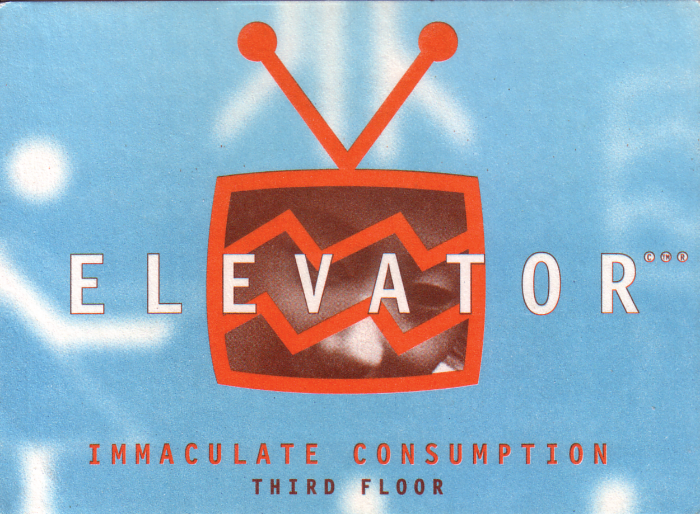

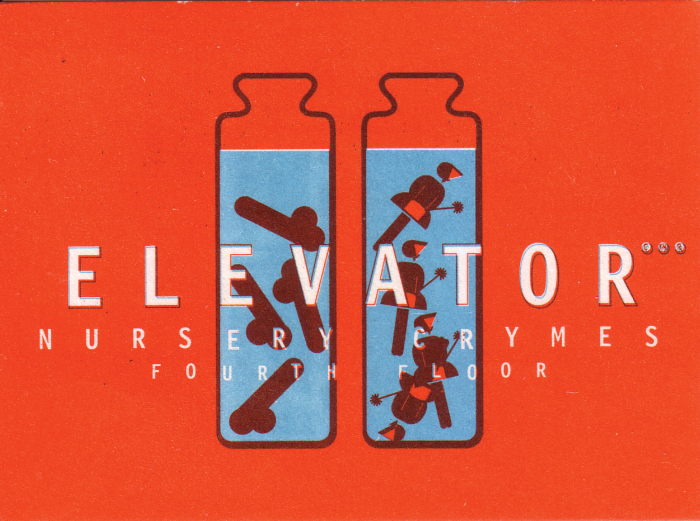

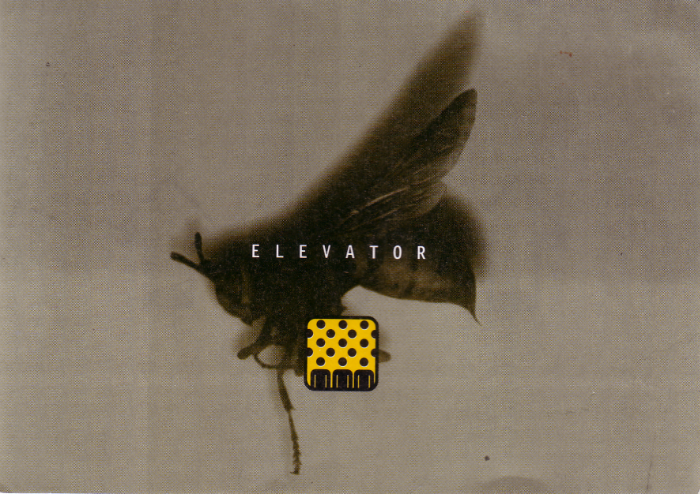

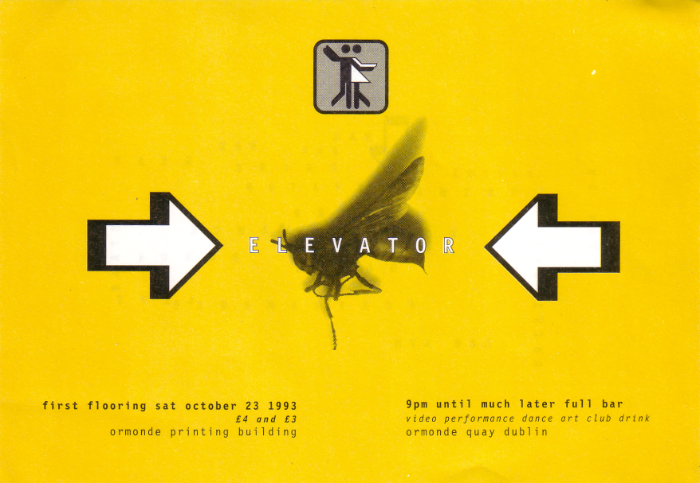

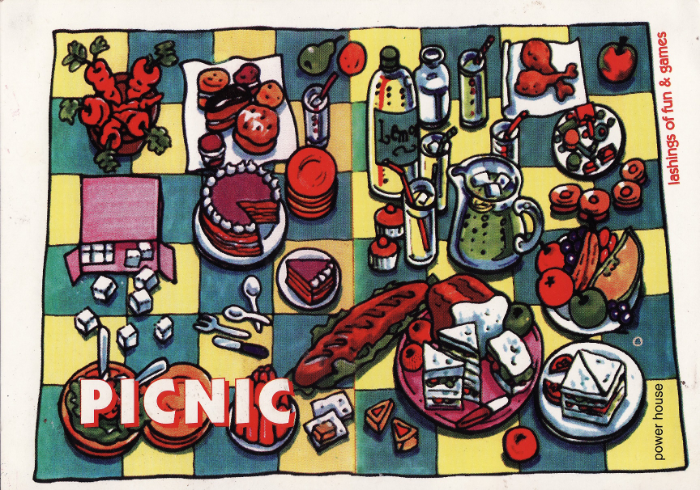

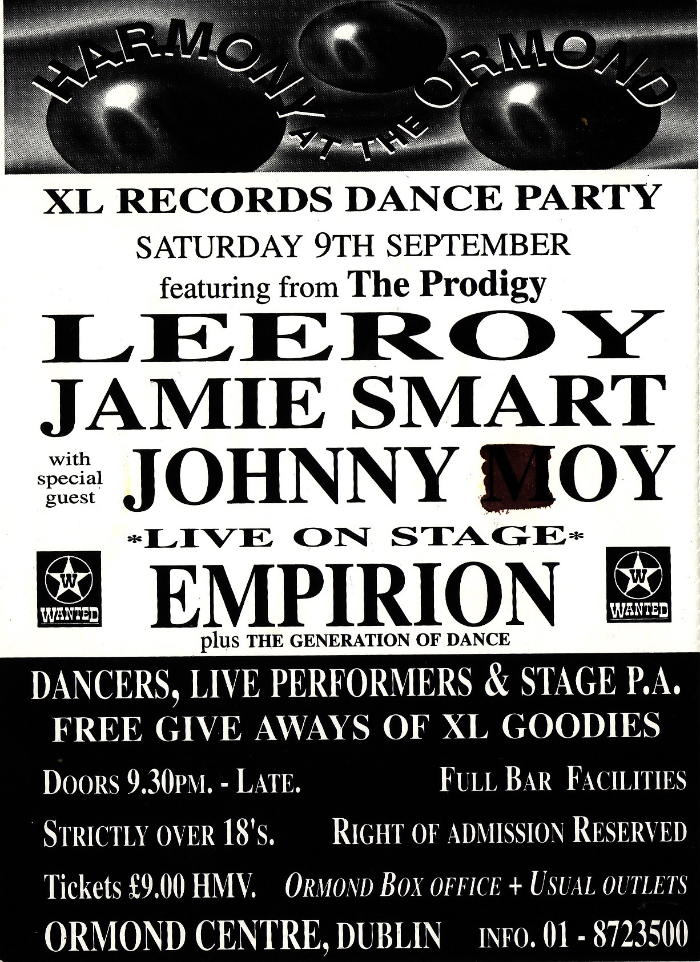

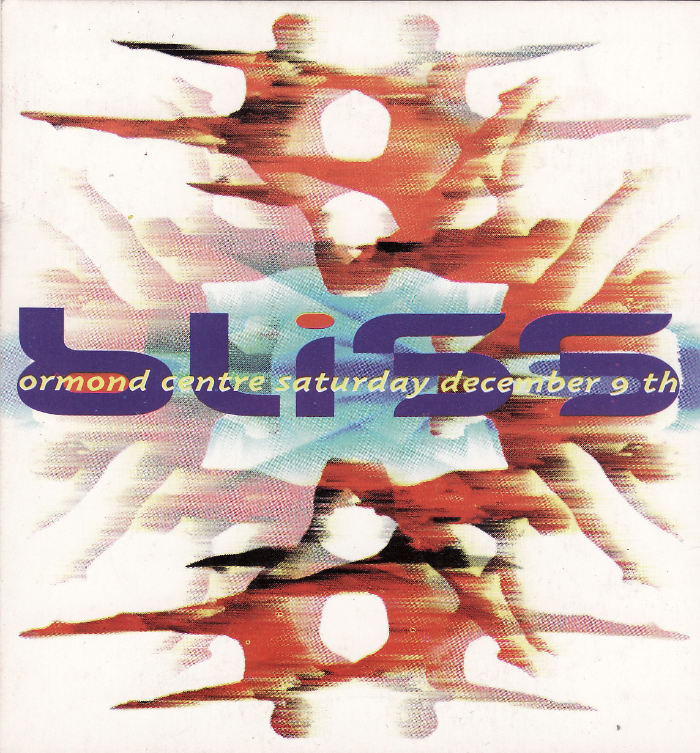

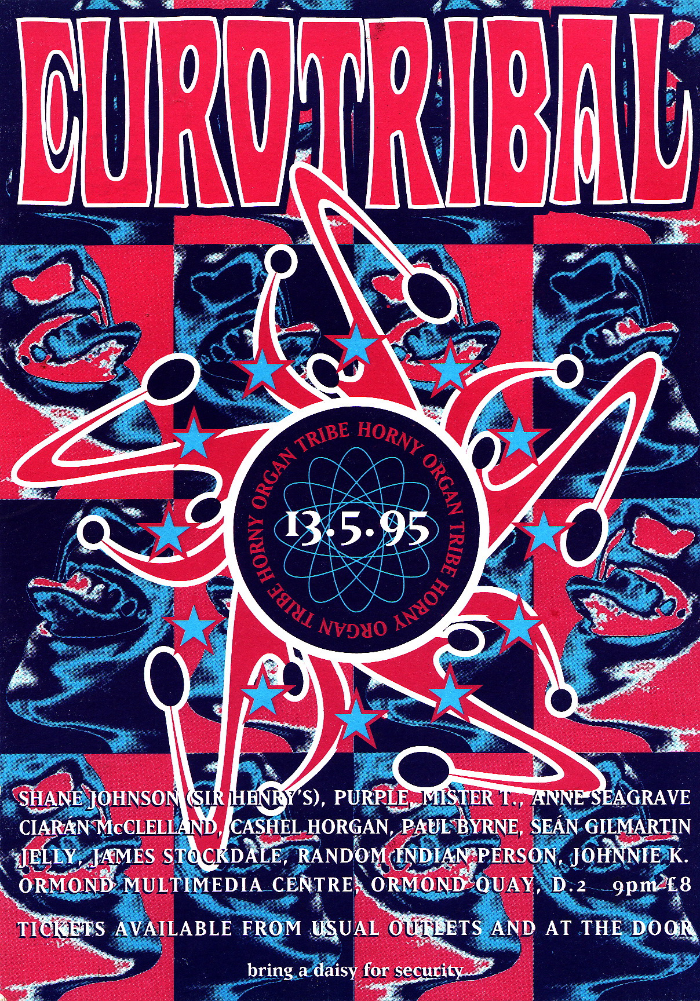

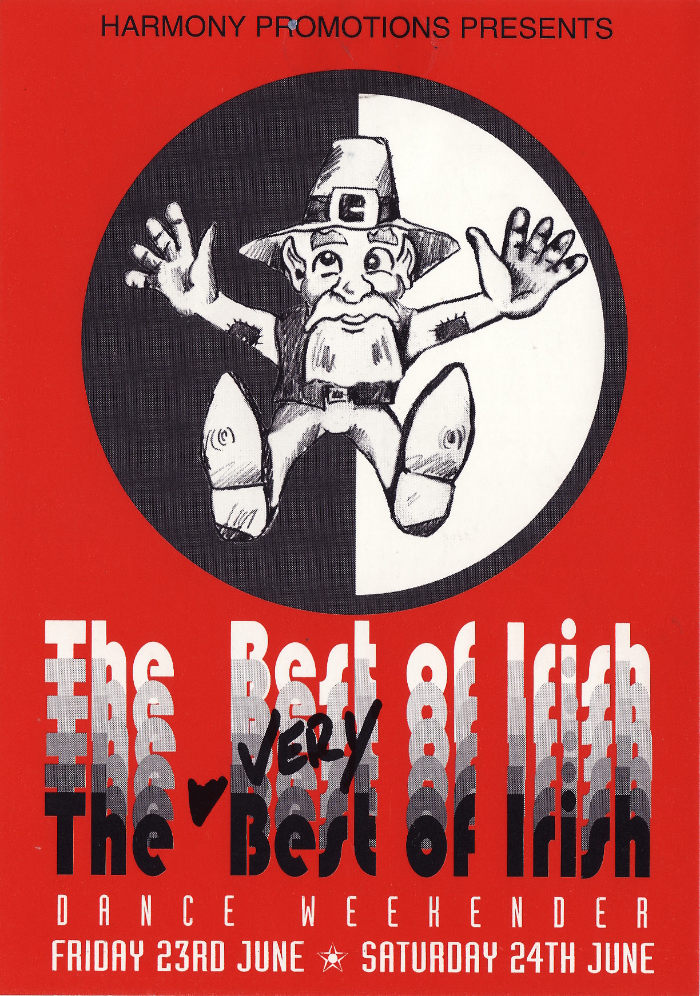

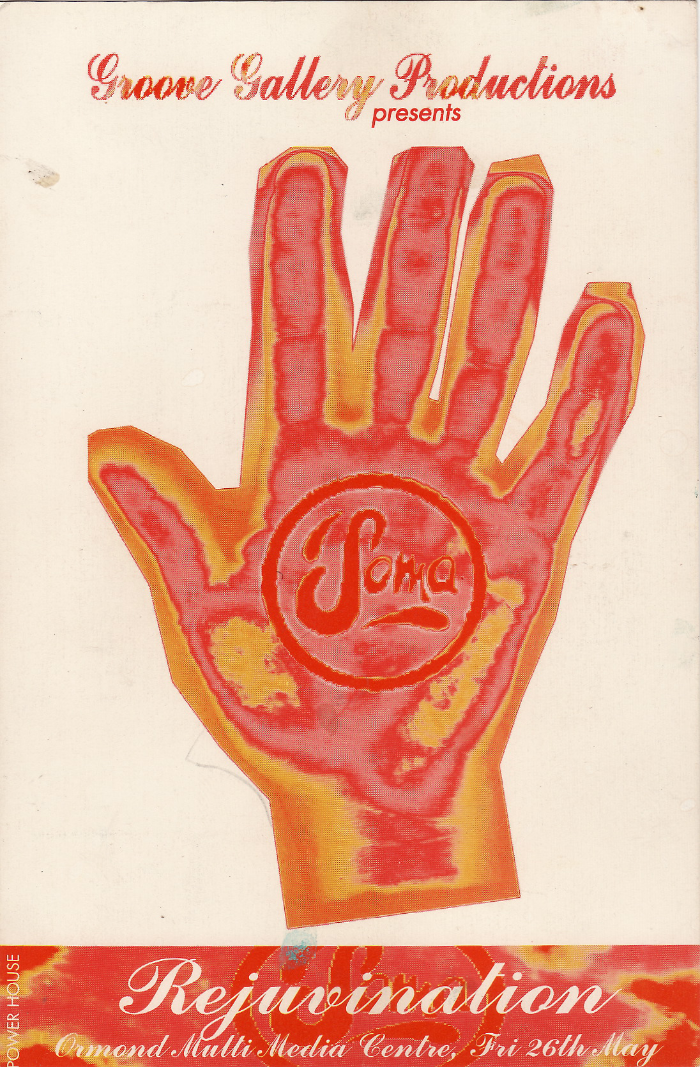

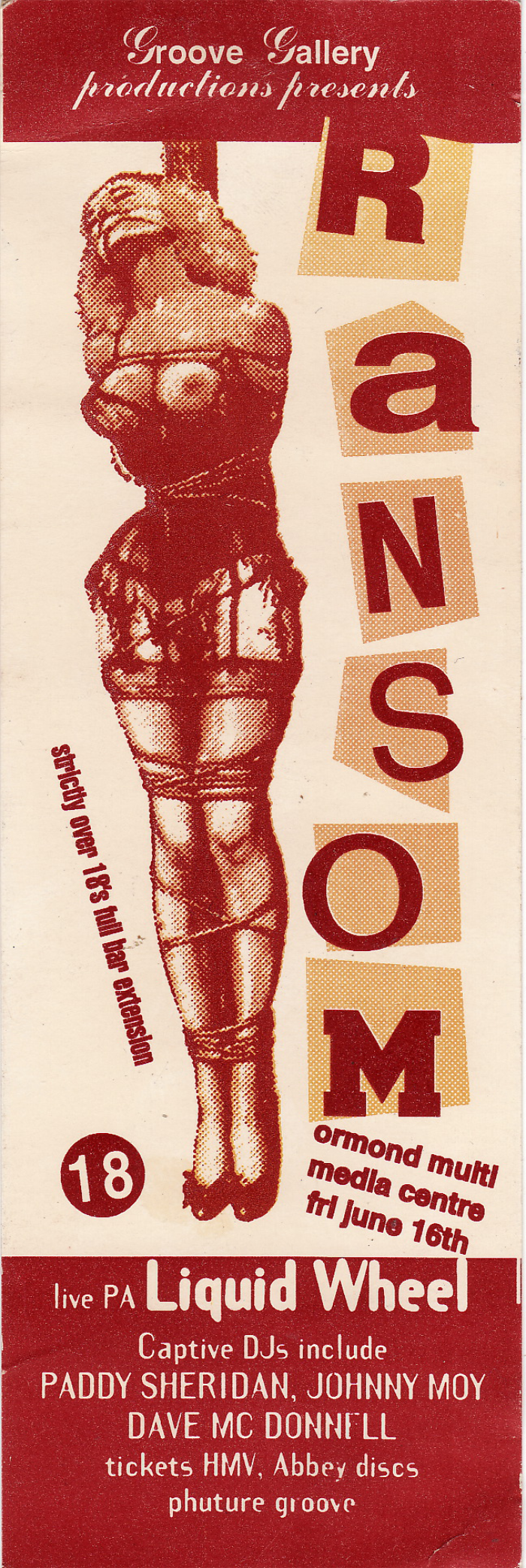

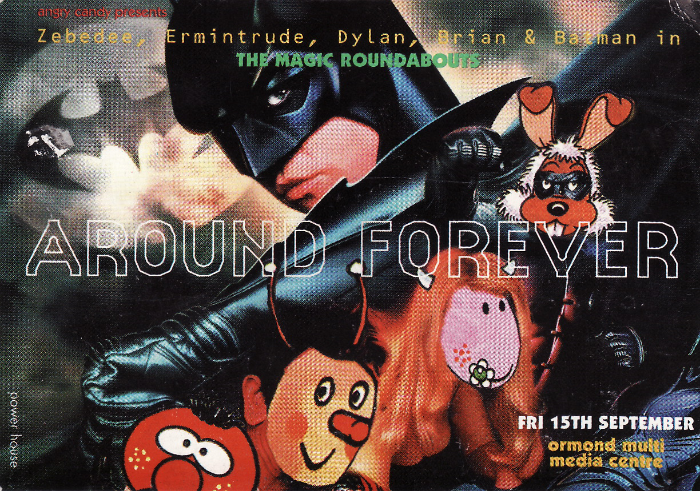

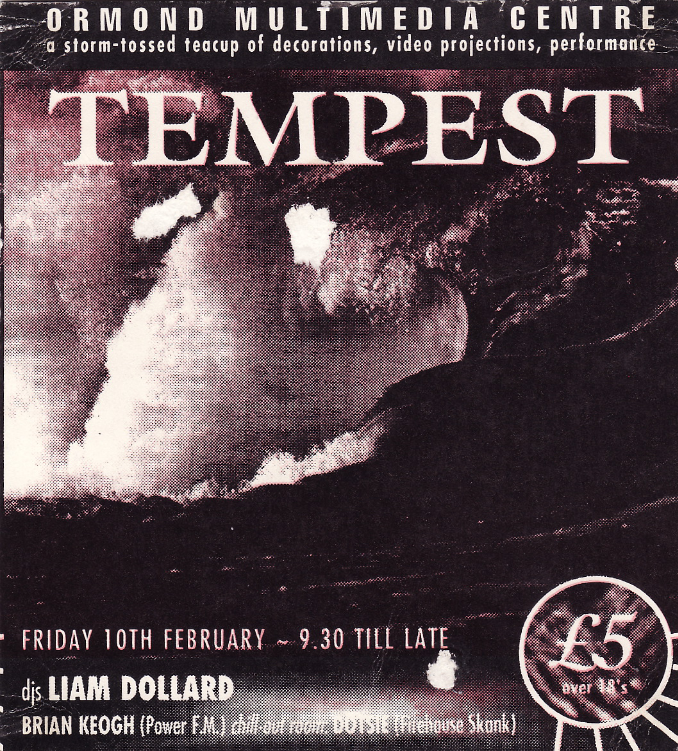

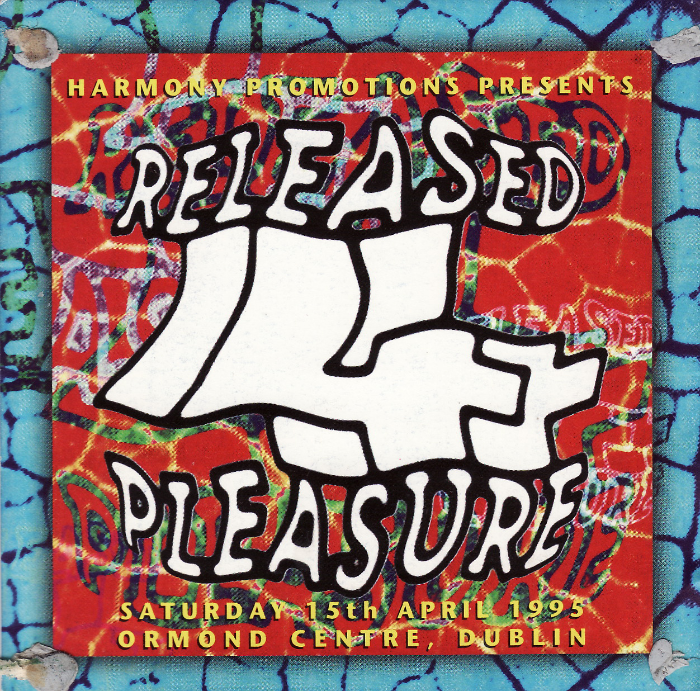

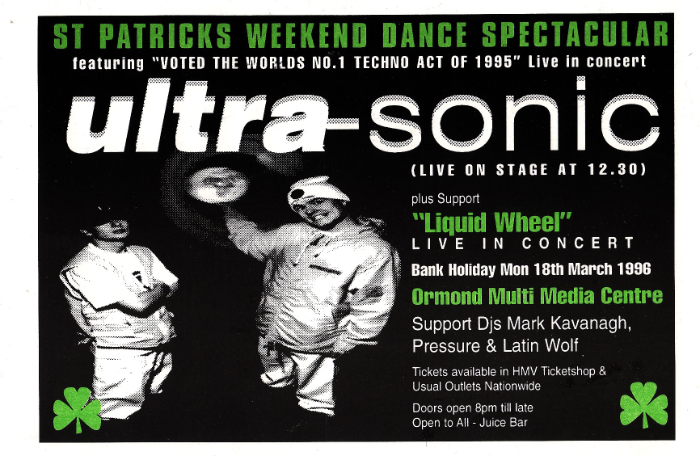

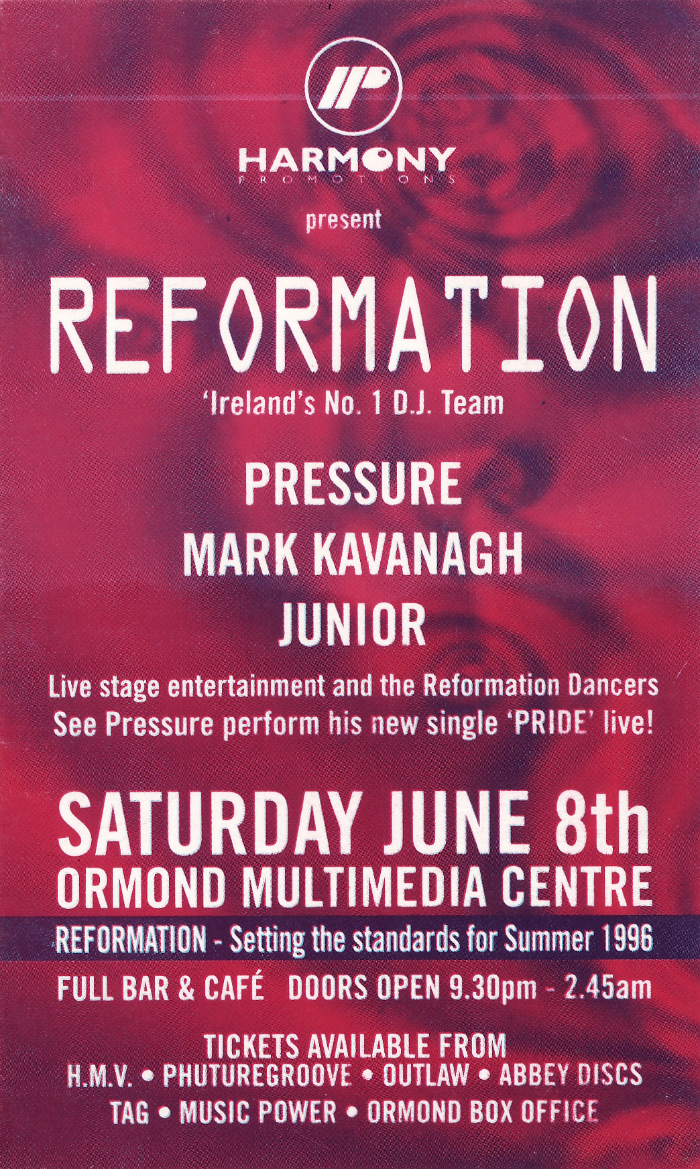

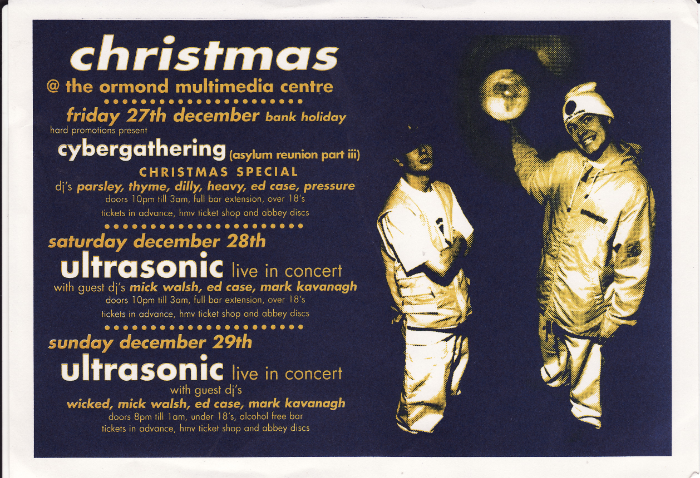

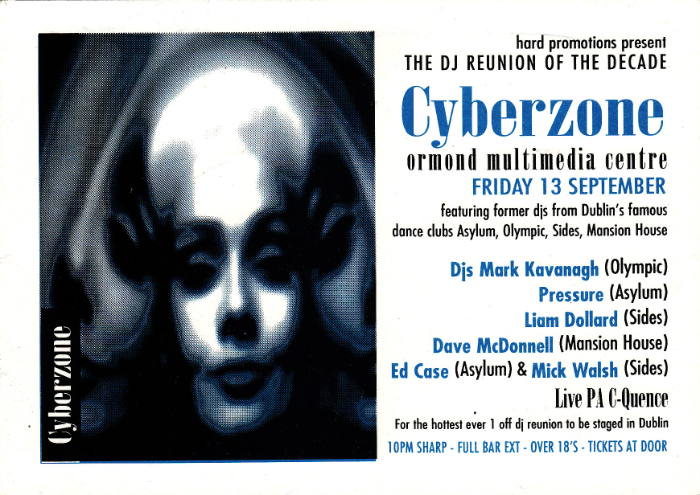

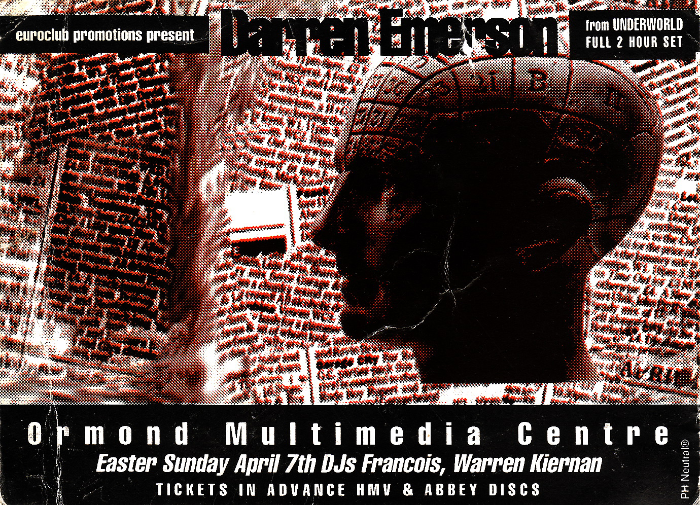

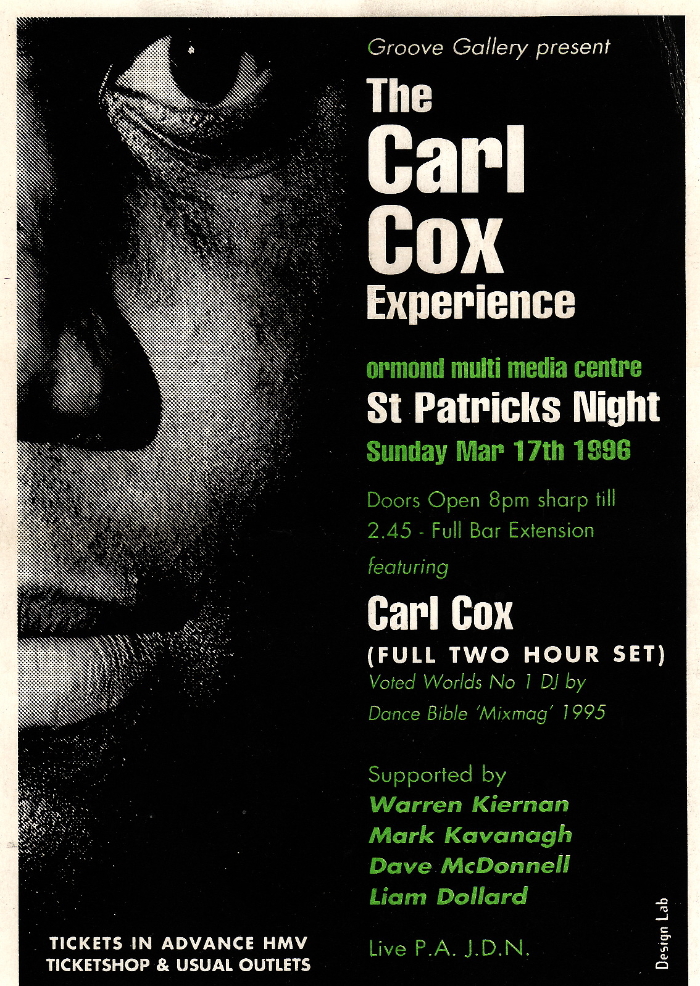

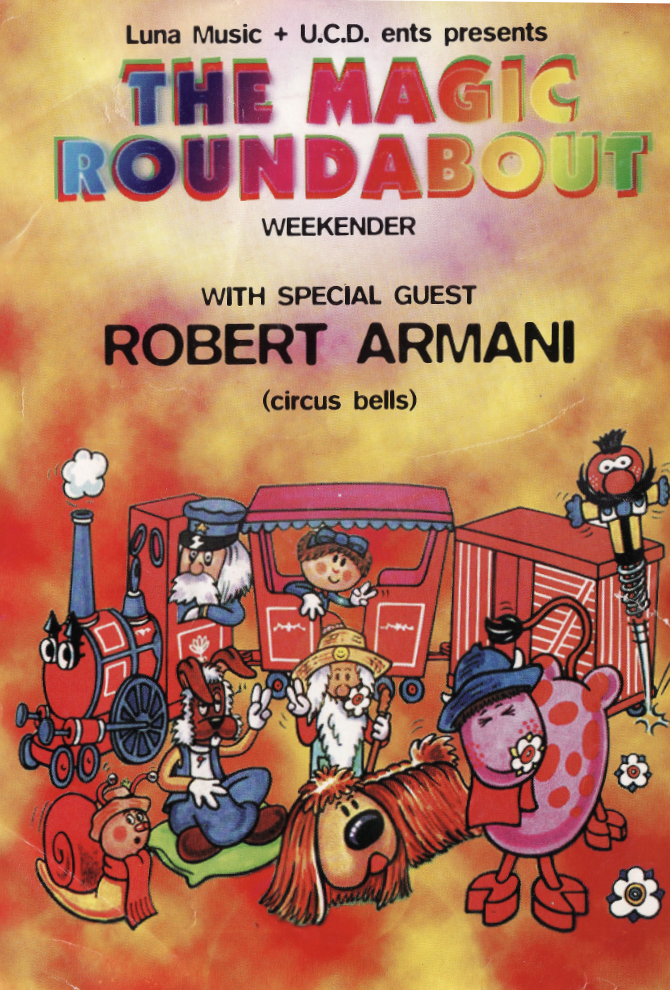

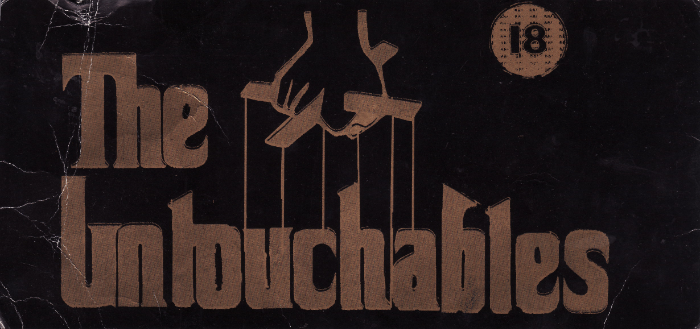

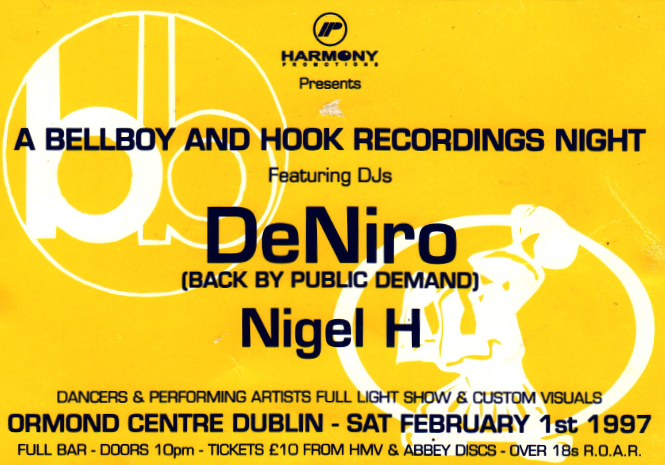

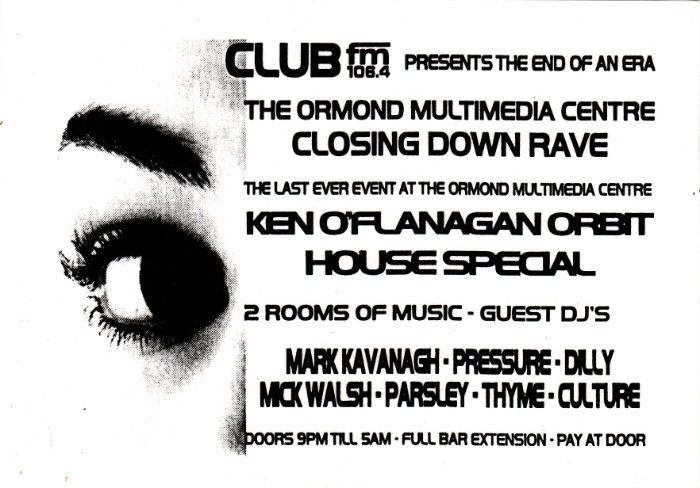

FLYERS

PHOTOS

Photos of Elevator at The Ormond Multi Media Centre by Seán Gilmartin (from Tonie Walsh Private Collection)

VIDEOS

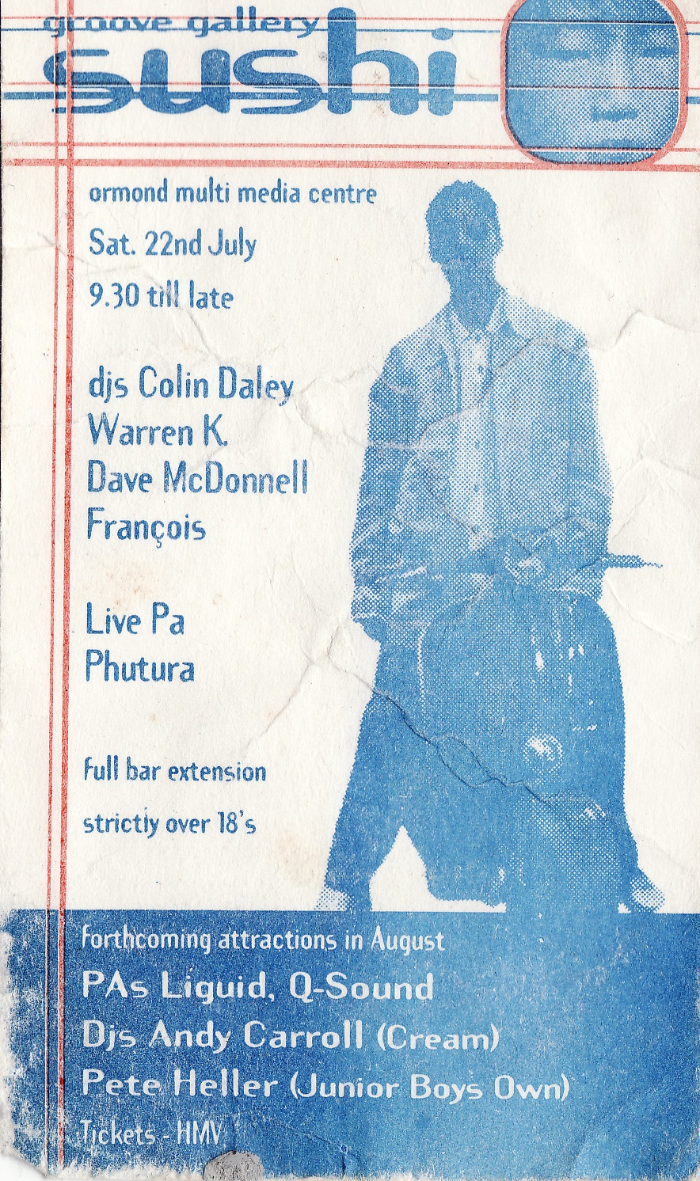

Warren K, Ormond Multimedia Centre, 1996

NR:GEX, Ormond Multimedia Centre, 1996

Ed Case, Ormond Multimedia Centre, August 1996

DJ SETS

Right click to open in a new window

Headspace at Ormond Multimedia Centre, 1993

JX, N-Trance & DJ Pressure – Ormond Multimedia Centre, 14 July 1994

Billy Nasty – Ormond Multimedia Centre, 25 July 1996

Tall Paul & Tony De Vit – Ormond Multimedia Centre, 16 March 1997

Last Night Of The Ormond – 14 June 1997 – Part One

Last Night Of The Ormond – 14 June 1997 – Part Two

Keno Flangan, DJ Orbit – The Last Night Of The Ormond, 14 June 1997

WORDS

Excerpt from the article ‘An eruption of pagan passion – The story of the Horny Organ Tribe’

Originally published on 909originals.com

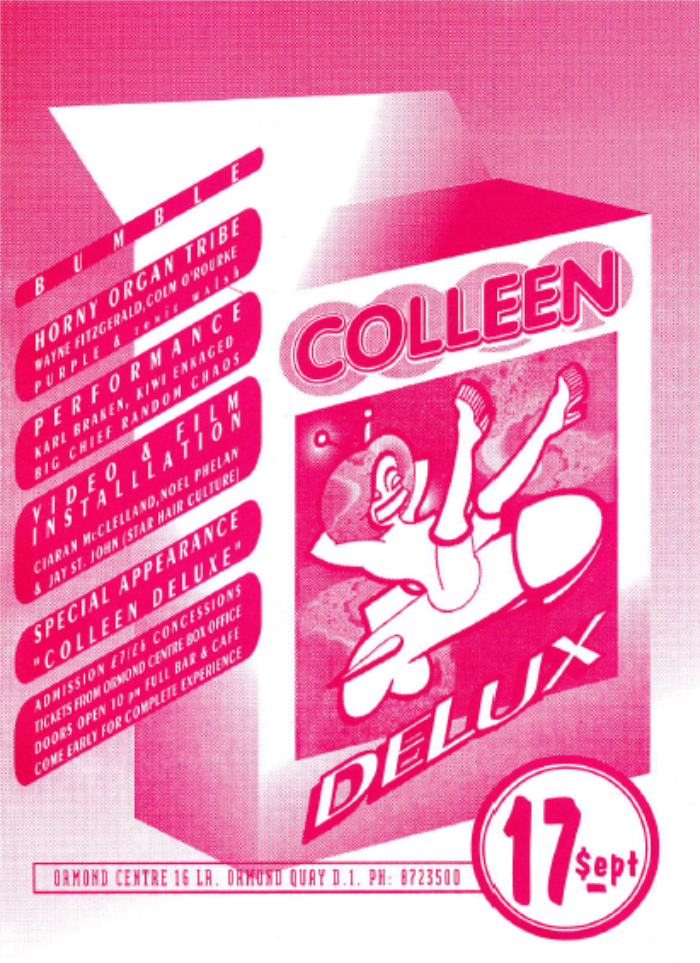

While Paddy Dunning had been a fixture on Ireland’s music scene since the early 80s with his Temple Lane Rehearsal Studios, his acquisition of an old printworks on the quays – rebranded as the Ormond Multi Media Centre – was arguably his most ambitious project to date. The opportunity for the Horny Organ Tribe to utilise the new venue was unmissable, as it presented an opportunity to ramp things up considerably, as the number of artists, performers and creatives pledging allegiance to the Tribe rose into double digits. H.O.T. at the Rock Garden ran for about 18 months altogether, before the Ormond became the main focus of attention.

Tonie Walsh: “Things very quickly progressed towards the Ormond Multi Media Centre, because within a couple of months – I’d say before the end of the summer – Paddy Dunning was in touch with us to ask if we’d like to do something. He had just got his hands on the Ormond Centre.

“There was something in the air, with all these magical things happening at the same time. We were so lucky – I’m not just talking about the Horny Organ Tribe – we in Dublin were all so lucky that we were able to access these big, open spaces.

“There were landlords that obviously wanted to make some money, but were also open to saying ‘go in there and surprise me, do something. And by the way, this is what the rent is’. We made a tonne of money for them of course – especially with Elevator, because I still have all the accounts.

“When we were doing the Rock Garden – and this is actually I think why we left – the split was really f**king onerous in favour of the venue, it was 60/40 in their favour. There was no way of making money out of it. Between myself and Purple, I think we made about £40 a night, after basically promoting the night, DJing, and paying people like Shelley and Mícheál Murray. Also whatever spare cash was around was put into painting tribal backdrops, and we would dress the venue up.

“The DIY aesthetic was very evident, and at Elevator it was even more so – we had a budget, so we could scale up our ambition. We went from having a budget of £100 a night in the Rock Garden to having a budget of £6,000, which was a lot of money in 1993. We had no sponsorship –commercial sponsorship only started to take root in the mid 90s.”

Aoife NicCanna: “I remember Tonie saying, ‘we’ve got a venue, and it’s massive’. It sounds unbelievable now, what we got to work with, but there were a few big venues cropping up here and there – about a year before we had been to see Primal Scream in the SFX, and of course you had the raves in the Mansion House.

“So it didn’t seem that unusual at the time to get the Ormond. It was an old warehouse, a great venue.”

At the time of its opening, the Ormond Multi Media Centre was unlike anything Dublin had seen to date. It incorporated offices for the arts and media sectors, rehearsal rooms, an art gallery, a café and restaurant, and a 1,000-capacity event space. ‘The place just pulsates with activity, and there’s this sense of sitting on something that’s about to explode,’ as the venue’s PR officer, Aoife Woodlock, told the Evening Herald at the time.

Tonie Walsh: “When we went to the Ormond, it was just a concrete shell. Everything had to be put in there. We weren’t going to downplay the low-tech industrial look of the place – that was one of the strengths – but it needed lots of stuff. In order to battle some of the sound issues, we started hanging drapes, and once we decided we needed to hang drapes, then we started working up the aesthetics of it.

“It was an enormous space – an old industrial print works – and it still had all the apparatus in it. Huge big chains along the ceiling to hold massive rolls of newsprint and things like that. There was a side room, which we operated as a bar area and chill-out lounge. We had a DJ in there playing R&B, things like that.

“And then you had this massive dance area, with podiums featuring all these impromptu performances. A lot of the time there was no announcement – a spotlight would move across the dancefloor and all of a sudden, there would be a woman dressed like a Greek goddess standing on top of the fire exit, singing some big trance tune, like Grace – Not Over Yet.

“Because Paddy Dunning only had a theatre licence – I actually got prosecuted under the Public Dance Halls Act later on, but that’s another story – we couldn’t do gigs without putting on some sort of performance in there. I mean, we wanted to, anyway – Paddy was sort of pushing an open door there.”

Shelley Bartley: “I had previously been to The Mansion House and the Olympic Ballroom and they were massive venues. This event was different. It had a more niche crowd, although at the same time, at this stage, the E-thing had really kicked in, sp the Ormond had loads of guys with their tops off.

“I used to dance in a cage there. There were big massive cages that you had to climb into, and I would be there all night. We were doing so much speed, I’m surprised I didn’t have a heart attack on one of the nights.”

Niall Sweeney: “The Ormond was an amazing place. It was really one of the last great standing concrete boxes, probably full of health and safety dangers, which of course weren’t even considered at the time.

“It was phenomenal, because it had that classic magic of a space, in which there were lots of separate spaces. It was also pretty robust. There were chains on the ceiling that used to carry the printing equipment, which that you could swing stuff out of – or people, like we did.”

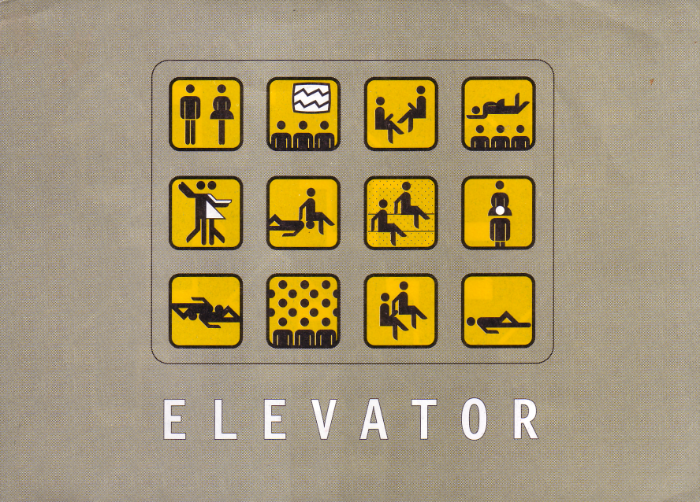

By late 1993, just months on from the formation of the Horny Organ Tribe, the troupe put on its first night – Elevator – following this up with a series of similarly-titled events over the course of the following year and a half, each of which saw a ramping up of the visual and performance aspects. As a H.O.T. press release from 1994 put it, ‘Picture the scene. You’re in a large, warehouse-type venue, up to your eyes in artificial additives [Ed – guarana, perhaps?] , bopping along to your beloved or looking for one, for the night at least. On all sides you’re assaulted by incredible lights, lasers and weird and wonderful film and computer-generated images on large screens….’

Tonie Walsh: “In the middle of the venue, sort of creating a semi-barrier between the art gallery, café, the front section and the dance floor, was this huge caged area with a big industrial lift. This was what gave the night it’s name, Elevator.”

Niall Sweeney: Myself and Blaise Smith – an amazing painter, who lives in Kilkenny now – did an installation piece called ‘Eternal Elevator’. It was a really simple random looping installation – we were interested in self-generating sequences. We would set up a series of clips, each topped and tailed with some kind of information, and the machine itself would then play one clip and look at what might be a good continuation from the previous one, a bit like dominoes. So you might get repetitions, something that makes sense, or something that makes nonsense.

“I think in the actual elevator itself, we had a tiny little screen with elevator-style icon graphics and a sequence of Muzak playing. Blaise wrote this amazing piece of classic lift Muzak.”

Tonie Walsh: “When I think back, we did four Elevators pretty much back to back, which given the amount of work involved, the programming and the investment, was just extraordinary.

“This was how I first met Panti Bliss. Rory O’Neill was living in Tokyo. He didn’t come back to Dublin until 1995, and so my first time meeting him was virtually, when Rory pre-recorded a piece, as Panti.

“Niall and his tech boys would bring over all this equipment from Trinity, set it up, and use a mixture of the pre-recorded stuff that Panti had sent over from Tokyo, as well as a video feed from around the venue, and feed it back to the cage in real time. That would then be mixed and projected back onto those perspex screens. It was some of the sexiest, most beautiful stuff I’ve ever seen, and we have no photographic evidence of it.

“We got these huge sheets of perspex – maybe three metres by two metres – and the back of them was slightly abraded. We hung them in series over the dancefloor in the Ormond Centre, and projected onto them. Because the perspex was slightly abraded, it held the image, but the image went through it as well. There was a level of transparency, but enough abrasion to give you a sort of solid figure.

“People used to smoke in clubs at the time – and we also had smoke machines – so at a certain point, the perspex would disappear, and you would just see these images floating in the air. It was really gorgeous.”

Niall Sweeney: “At Trinity, I was part of an experimental new media group. I was brought in as the creative lead rather than just focusing on design. We worked with the latest technology – the latest Macs, cameras, and early touchscreens. Looking back, it seems really gritty, but it was incredible.

“Tonie asked me to do the graphics for Elevator, and we had all this amazing equipment. So, for the first Elevator – or maybe it was the second one – on the Friday night, we secretly moved all this amazing computer equipment from Trinity to the Ormond, and had to get it back the next day.

“It was a way of progressing and experimenting with the equipment. But also, we were young, so it just seemed like, ‘yeah, we can do that’, you know?’ Some of our friends had larger cars, so we would load the equipment, cover it with blankets, and then sit on top of it. But it all worked out.”

“Actually, much later on, in the 2000s, when I met Jenny Jennings – one of the directors of This is Pop Baby and a great friend – she remembered it was a transformative thing for her. All the visual effects, and the projections – she was amazed that this could be even happening in Dublin.”

As journalist Matthew Wherry noted in late 1994, the Elevator series of events was the ‘most progressive parties/club events Dublin had yet scene – both in their use of the latest multimedia technology and in the decadent sexual energy that the Horny Organ Tribe bring to all their projects’. A key aspect of that energy was about encouraging those present to become part of the performance – allowing themselves to get swept away in the ritualistic abandon of the night.

Tonie Walsh: “We encouraged people to dress up, and when I look at the photographs, people wore body paint, face paint, there were corn dollies, there were guys that were dressed as straw men, who looked like mummers or something.

“People responded to that. I always feel when I’m DJing, I want to be down on the dancefloor. I hate DJing on a stage with a big spotlight on me, where I feel pressurised to be a sort of performing monkey or something. I’d rather be down on the floor, almost in darkness. That’s the vibe. So that then begs the question, how can you entertain people visually, without the DJ being the sole reference?

“I don’t want to come across as self aggrandising, but it was really breaking new ground. Nobody had tried any of this before. That mixture of theatre and performance, and site-specific installations – nobody had tried it then, and actually, very few people have tried it since.”

Aoife NicCanna: “If you went to Tonie and said, ‘I have a great idea’, he was always ‘let’s do it’, he never really worried about the financial side of it. He was always looking at the big picture, and what we could do.

“There were people doing performance art, there was somebody else doing massages. There were people volunteering – sometimes they were making money from it, and sometimes they were just doing it for the love of it.”

Niall Sweeney: “There aren’t many photographs from back then, cause that wasn’t a concern, you know? Also, thank God there weren’t any photographs…!

“When you’re in the thick of an evening, so much disappears – in terms of the sellotape and the bits of stuff trying to hold up that perspex screen, you know? Whatever it takes to create the experience. It’s kind of magic. If there were an actual photograph of it, it would probably look shockingly awful.

“Elevator achieved a mythological status for all sorts of reasons, and I think that’s great because people remember it for the feeling and the transformation that was happening, both individually and as a group. It had a collective impact.”

SUPPORT ANALOG RHYTHMS: If you like what you see, why not pledge your support below to keep ANALOG RHYTHMS up and running. You can make a one-time donation or a monthly or yearly contribution. 🙂

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

One thought on “The Ormond Multimedia Centre”